Investment Philosophy

Value investing is an investment paradigm that involves buying securities whose shares are underpriced based on fundamental analysis. In other words, it means identifying opportunities to buy a dollar for fifty cents. We find many of our opportunities in the stock of public companies that sell at discounts to book value, sell for low multiples of earnings, and have high returns on equity. This approach is not new. For nearly a century, the Grahams, Fishers, and Buffetts of the world have demonstrated the effectiveness of this long-term value investing approach. Our objective is to achieve long-term outperformance of the S&P 500 including dividends.

The Fund’s investment strategy is based on our core principles which, over the long run, will help to generate higher risk-adjusted returns than other investment managers.

We look at each stock purchased as owning a percentage of the business.

We recognize that a stock is not an asset in itself but represents an interest in a business. This mentality enables us to focus on company fundamentals to evaluate the business by assessing its real-world economic prospects, cash flow drivers, competitive threats, future opportunities, barriers to entry, and other relevant factors. We are much less concerned with secondary matters such as price trends, volatility, performance relative to other stocks or market indices, or other technical aspects. A company’s stock price eventually will reflect the actual results and future prospects of the underlying business.

Most fund managers reach for a quantitative screening tool to narrow their search for undervalued securities. Common screens, such as low enterprise value (EV) to EBITDA, high return-on-equity (ROE), or increasing profit margins, may narrow the search but do not always result in a cheap pool of securities. This common approach to eliminate expensive securities introduces what statisticians classify as type I errors (incorrect rejection) and type II errors (incorrect inclusion). Many cheap stocks are overlooked (type I error) and other stocks that screen cheap are cheap for a reason (type II error). Howard Marks reminds us to use second level thinking. If most funds screen on similar metrics to find their cheap stocks, those companies will be oversubscribed and will not be cheap.

Our initial filter is to evaluate positions in the portfolios of the top value investors in the world: what are they buying, what are they selling? Within the high turnover environment that eclipses most of finance, this would be completely ineffective. However, value investors build positions over quarters and years and might hold a single position for a decade or longer. Every 90 days the SEC requires institutional investors with over $100M under management to file a 13F report disclosing each U.S. holding. A detailed quarterly analysis covering nearly 100 global superinvestors quickly narrows thousands of potential opportunities to a few hundred that are being actively acquired by the most successful investors of all time.

In this highly competitive industry, narrowing our scope this way allows us to fish in the right pond of investments. Many known superinvestors hold very concentrated portfolios, so a new position may constitute 10% or more of a multibillion-dollar portfolio. This method still provides hundreds of securities to research and choose from. It also reduces our error rate while increasing the likelihood of discovering the very best opportunities.

We look at market volatility as our friend and take advantage of mispriced securities.

It is often said that price is what you pay and value is what you get. This view is deeply embedded in our investment practices. We will wait patiently for a good opportunity at the right price. Although we seek to invest in great businesses, not all great businesses are good investments.

We are often asked what makes a great stock. One popular misconception is that great companies are great investments, and the corollary that lousy companies are bad investments. But owning great companies is a bit like motherhood and apple pie: it makes for a nice, crisp, and comforting investor presentation. Most portfolio managers feel good and claim to sleep better when they own great companies, and it is true that few managers get fired for buying great companies. Lose money on a great company, and it is the company’s (or the market’s) fault. Lose money on a lower quality company, and it is the manager’s fault. The trouble is that, with everyone focused on a few great companies, those companies tend to be overpriced and are often terrible investments.

It is important to note that while some investment managers take pride in owning the hottest stocks in the market, we typically have a different view. Many of our best ideas are hidden where nobody else is looking. It is much easier to find an undervalued asset when it is a relatively boring firm operating under the radar. Although this approach may make us less exciting guests at a dinner party, it is more likely to yield above average returns, which counts for much more to us and our investors.

Fortunately, there is a lot more to investing than buying great companies. Anyone can screen for strong financials, but it is much more difficult to screen for great management and analyze the deep fundamentals of the business. It is a much wiser strategy to buy great companies when they are temporarily out of favor. Buying out-of-favor great companies will naturally lead to increases in portfolio volatility but, with our long-term view, any monthly or quarterly fluctuations should smooth out over time. We believe our investment strategy will generate superior long-term risk-adjusted returns.

Our goal for the Fund is to earn returns that outpace the market. We are looking for great investments – not only great companies. As value investors, we take a very pragmatic approach to investing: a stock is great when its market price is below the firms’ intrinsic value.

We employ a margin of safe policy to investing as a means to limiting our downside risk.

We make no attempt to time the markets, as this nearly always leads to disappointment over the long-term. Instead, we use a margin of safety before making any purchases to limit any downside associated with an investment. We believe investors should not be excessively pleased or troubled by short term swings in stock prices, and so we will establish each Fund position with the expectation of long-term appreciation. Our favorite holding period is forever.

We minimize the use of leverage.

Leverage will be kept to a minimum. Leverage increases portfolio volatility, encourages unnecessary short-term speculation, and can exacerbate market swings both up and down. We focus on the long-term, and the first rule to outperforming the market over the long-term is to exist over the long-term. Obvious or not, this point is not well understood in today’s marketplace.

We concentrate on our best ideas.

A portfolio that consistently increases its number of positions becomes more likely to deliver average results. After all, how can one outperform the market if he holds the entire market? We understand the proper role of diversification, but believe that role should not be overplayed. We focus on our best ideas and avoid acting on ideas that strike us as only average. Not only is this likely to maximize returns, but it also reduces frictional transaction costs and forces market discipline.

Consider, for example, the typical holdings of any public mutual fund, or of many private hedge funds. Although such funds typically own hundreds of stocks, most of their holdings make only a marginal contribution to the fund’s return – for two simple reasons: (1) relatively few perform well; and (2) their position sizes often are far too small to contribute significantly to the fund’s return.

In many cases, the true marginal contribution of a portfolio holding may be negative. Underperformers (be they stocks, people, or anything else) consume vastly more time and attention than winners. Instead of proactively searching for the next big winner, a portfolio manager holding many different stocks often must reach to each little disappointment and crisis. For this reason, we will concentrate the Fund’s capital behind our best ideas, freeing up our time and attention – our most scarce and precious resource – so that we can find the next big winner.

Operational Philosophy

Peterson Investment Fund I, LP is built on a foundation of integrity designed to last for generations. PIFI focuses on minimizing portfolio turnover, minimizing expenses, and strategically aligning incentives. This practice over the long term will directly enhance returns and provide significant value to our clients, the limited partners (LPs).

Our communication includes quarterly letters that present salient quantitative information and annual letters with detailed commentary regarding the fund. Quarterly statements, an annual audit, and K-1 or relevant tax documentation are provided by our service providers.

We limit portfolio turnover with a focus on long-term capital appreciation.

Our sound fundamental analysis allows us to minimize movement and maximize gains. We do not attempt to speculate on short-term movements in market prices but instead become long-term owners of the underlying businesses. Our ideal holding period is forever and so, we are proud to say, we are not our prime brokers’ most profitable client.

Minimize expenses and frictional costs for investors.

Unnecessary frictional costs (e.g. avoidable taxes, high transaction fees, etc.) can significantly erode investor value over time. Reduction of 100 basis points in frictional costs can provide significantly greater returns for a typical Limited Partner (who contributes $1,000,000 to the Fund, for example), potentially saving more than $100,000 in a single decade. We see no reason to subject clients to these expenses and many reasons to avoid them. Taxes and transaction fees are two such expenses that – like the friction of a brake pad against a wheel – will slow down the capital appreciation process.

We work to align investor and manager incentives and eliminate conflicts of interest.

Alignment of general partner and limited partner interests is a top consideration in every operational decision. The unique structure of PIFI incorporates an annual hurdle rate, a high-water mark provision, and an emphasis on performance-based compensation to achieve alignment objectives. A shared pursuit helps avoid conflicts of interest and allows us to maintain the integrity of the fund over the long run.

Proper incentives can significantly enhance and align motivations. Specific tangible, financial enticements have particularity notable power to alter actions or desires. A management fee-based firm will attract highly paid and very successful sales people because raising capital can deliver significant bonuses. Similarly, compensation based on long-term performance will attract those able to deliver long-term market outperformance. We have aligned ourselves with the latter. Compensation is earned only after reaching new all-time highs (high water mark) and on annual returns above 5%. The economics are simple: we only make money when you make money.

Alignment of Interests

Alignment of general partner and limited partner interests is a top consideration in every operational decision. The unique structure of PIFI incorporates an annual hurdle rate, a high-water mark provision, and an emphasis on performance-based compensation to achieve alignment objectives. A shared pursuit helps avoid conflicts of interest and allows us to maintain the integrity of the fund over the long run.

Proper incentives can significantly enhance and align motivations. Specific tangible, financial enticements have particularity notable power to alter actions or desires. A management fee-based firm will attract highly paid and very successful sales people because raising capital can deliver significant bonuses.

Similarly, compensation based on long-term performance will attract those able to deliver long-term market outperformance. We have aligned ourselves with the latter. Compensation is earned only after reaching new all-time highs (high water mark) and on annual returns above 5%. The economics are simple: we only make money when you make money.

Investment Process

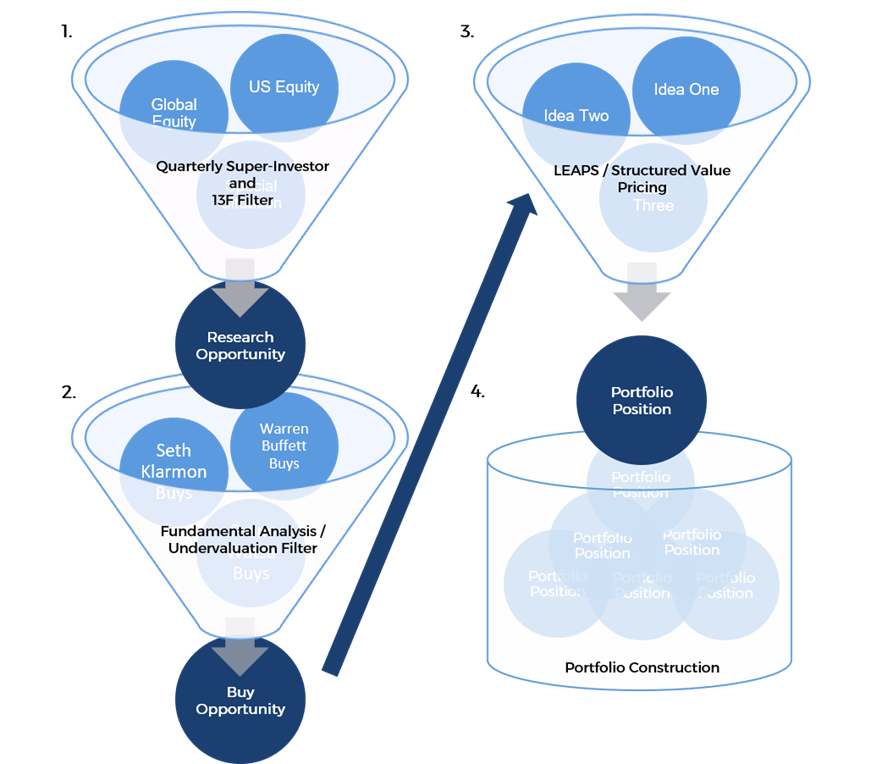

Step 1: Understanding Superinvestor and 13F Reporting

Our objective is to uncover the few market securities so deeply undervalued by the marketplace that they warrant a long-term position in our portfolio. Today the NYSE and Nasdaq list more than 5,000 actively traded companies and approximately 10,000 public securities exist in the U.S. alone. Most are fairly valued, most of the time. Without using tools to efficiently narrow the scope, a fund might search for years before identifying a single desired “cheap” stock.

Most fund managers reach for a quantitative screening tool to narrow their search for undervalued securities. Common screens, such as low enterprise value (EV) to EBITDA, high return-on-equity (ROE), or increasing profit margins, may narrow the search but do not always result in a cheap pool of securities. This common approach to eliminate expensive securities introduces what statisticians classify as type I errors (incorrect rejection) and type II errors (incorrect inclusion). Many cheap stocks are overlooked (type I error) and other stocks that screen cheap are cheap for a reason (type II error). Howard Marks reminds us to use second level thinking. If most funds screen on similar metrics to find their cheap stocks, those companies will be oversubscribed and will not be cheap.

Our initial filter is to evaluate positions in the portfolios of the top value investors in the world: what are they buying, what are they selling? Within the high turnover environment that eclipses most of finance, this would be completely ineffective. However, value investors build positions over quarters and years and might hold a single position for a decade or longer. Every 90 days the SEC requires institutional investors with over $100M under management to file a 13F report disclosing each U.S. holding. A detailed quarterly analysis covering nearly 100 global superinvestors quickly narrows thousands of potential opportunities to a few hundred that are being actively acquired by the most successful investors of all time.

In this highly competitive industry, narrowing our scope this way allows us to fish in the right pond of investments. Many known superinvestors hold very concentrated portfolios, so a new position may constitute 10% or more of a multibillion-dollar portfolio. This method still provides hundreds of securities to research and choose from. It also reduces our error rate while increasing the likelihood of discovering the very best opportunities.

Step 2: Performing Fundamental Analysis

Sometimes it is easy to understand why superinvestors are buying (“In”). Other times, it is easy to see that the firm is outside our circle of competence (“Too Hard”). Fundamental analysis confirms attractive opportunities. Perhaps the intrinsic value based on discounted free cash flows is much higher than current market prices or maybe high returns on equity and low earnings multiples appear attractive. Corporate financial practices, like aggressive buybacks (what Charlie Munger refers to as corporate cannibalism) or spinoffs, might be further increasing the value of an opportunity. Finally, qualitative features such as shareholder-friendly management, owner-operators with exceptional capital allocation capabilities, positive feedback loops, and long-term margin protection may also exist.

Step 3: Applying Structured Value

This structured value method requires extreme patience. Rather than making outright stock purchases through limit or market orders, we sell insurance on the shares we want to buy that might extend for 24 months or longer. We engineer these contracts by combining various put options or related products and selling the contracts to counterparties. We collect a premium for the contract immediately and commit to purchasing their undervalued securities in the future, if they remain below our specified price. Because market conditions are volatile and counterparties can be fearful, owners of stock are sometimes willing to overpay irrationally for downside protection on wonderful businesses. So, when there are opportunities to obtain large insurance premiums on quality firms at attractive prices, we sell the contracts for your benefit.

Structured value provides us with an advantage over the traditional buy-and-hold strategy. We are paid a premium up front that reduces our net purchase price to a level that is often below the market price. Sometimes we are able to purchase stock for a net price lower than any that has ever existed in the market. As shares appreciate, a lower entry price will ultimately lead to higher returns.

A simple formula depicts how we achieve this lower net cost:

Net Cost of Stock = Commitment Price Paid – Premium Received

The counterparties that buy our contracts vary, from companies and other funds, to speculators betting on equity declines. For example, a life insurance firm may wish to protect their portfolio of stock from a market decline to maintain liquidity for potential claims payouts. They can use our contracts to achieve this objective. In exchange for risk mitigation, we gain a premium and access to the underlying stock at a discounted price.

Structured value will be very attractive at times and less advantageous at others. We will not participate in any market unless the prices are in our favor. We remain fundamentally based in value. Additionally, we may purchase equity via traditional means or other advantageous structured products. When no structured products exist, we will not hesitate to make use of market and limit orders when it is beneficial to the limited partners.

Step 4: Portfolio Construction

A half century ago, PhD physicist John Kelly identified a quantitative approach to asset allocation while working with Bell Labs. The Kelly Criterion states:

Percent of Bankroll Allocation = Edge/Odds

The Kelly Criterion suggests that one can optimize a position size given a known bankroll or portfolio net asset value. There are subjective limitations, such as probability and magnitude of positive and negative outcomes, but Kelly provides a framework for evaluation.

Charlie Munger often references the great 19th century German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, whose maxim “man muss immer umkehren” translates to “invert, always invert.” Through inversion, one can use the Kelly Criterion to derive optimal portfolio diversification ranging from four to 15 positions. This is a far greater concentration than what is practiced by many in the portfolio management industry and results are likely to be superior.

While the Kelly Criterion is designed to maximize long-term growth and prevent ruin, it makes no attempt to reduce volatility. As William Poundstone explains in his book Fortune’s Formula, “The full-Kelly stands a one-third chance of halving her bankroll before she doubles it.” Applying Kelly to your own portfolio requires a strong stomach. The implications are straightforward: when the odds of winning are in your favor, you must bet big.

Many superinvestor portfolios exhibit the characteristics of Kelly modeling with allocations of 20 to 50% remarkably common. Presenting at the VALUEx conference in Switzerland, in January, I used the following details from December 2014 to illustrate this point:

The Kelly Criterion guides our position allocation. Many of our own holdings begin around the 10% level and our long-term investment philosophy allows gains to compound. A single position has the potential to become a sizable component of our portfolio. This intentional concentration, over the long-term, will allow us to achieve our objective of outperformance.